Next Level Design

Skill and passion concentrated into just 0.02mm.

Tengu-jo Dial

Hidakawashi Co., Ltd

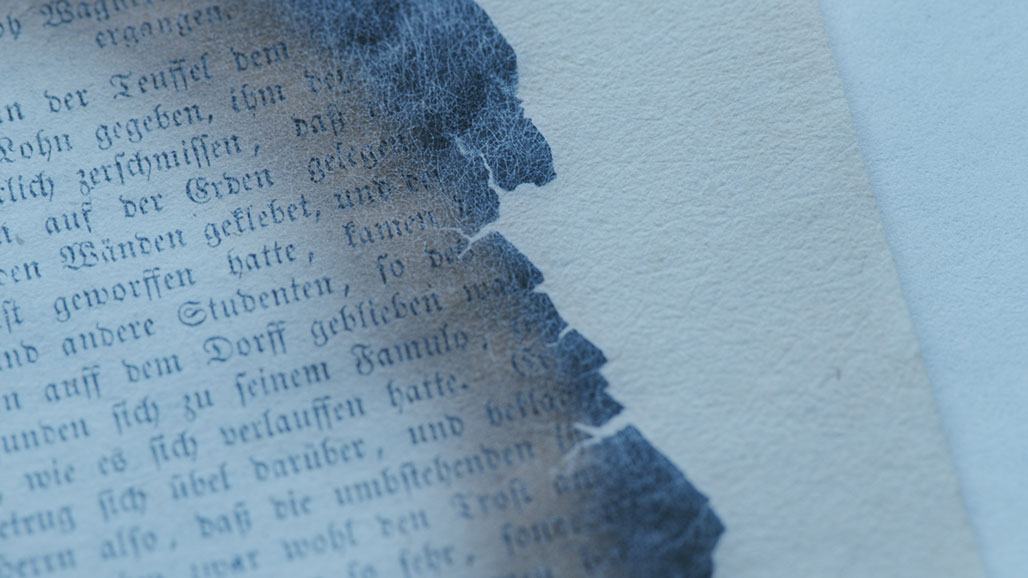

Just 0.02 millimetres thick. Weighing just 2 grammes for a one-square-meter sheet. An ultra-thin washi, Tengu-jo paper is light permeable and can be dyed beautiful colours. When used for the dials of The CITIZEN brand, it imparts a rich variety of expression to Eco-Drive, CITIZEN’s proprietary light-powered technology. We spoke to Hiroyoshi Chinzei, the fifth-generation head of Hidakawashi , the company that produces this ultra-thin yet highly durable paper in Hidaka beside the clean-flowing Niyodo River in Kochi Prefecture.

Watch the movie.

From hand papermaking to machine papermaking.

It’s about responding to a range of needs.

What sort of washi do you make at Hidakawashi?

Our mainstay product is Tengu-jo, an ultra-thin washi made from kozo [the paper mulberry plant]. We also make different kinds of washi for shoji screens and for wrapping paper.

Looking around your factory, I see that your washi is being made by machine rather than by hand.

Yes. In the old days, farmers often used to make washi by hand as a side job. Our business got its start when several farming households got together, formed a cooperative and moved to this area… When you make paper by hand, you’re forced to make one sheet of paper at a time. Inevitably, you end up with inconsistencies in the thickness and size of the sheets. Demand for machine-made washi went up because people wanted a continuous roll of paper that was standardised, offered greater freedom with respect to size, and could be incorporated to into mass-produced products. That’s the reason we installed our proprietary paper-making machines. That was back in 1969, and we’ve been focused on washi and nothing but washi ever since.

How does your washi differ from the handmade variety?

The process is pretty much the same until the point where we put all the ingredients we have prepared into the papermaking machine.

All the makers of washi make products with unique characteristics. The biggest difference with us is the sheer effort we’ve put into making washi that’s thin and transparent.

Can you explain how you achieve a higher level of transparency?

We spend an awful lot of time on the preparation of the ingredients—carefully removing small pieces of dirt and other impurities using the human hand and eye. Most makers of washi only do this once, at the bark-washing stage. We remove the impurities three times, once while washing, once after washing and again before putting everything into the papermaking machine. That is why we’re able to produce standardised thin washi with a high level of transparency, and with thick fibres that aren’t all tangled up. Life would be a lot easier if we used chlorine for bleaching, but since any bleach left in the paper mixture can cause discolouration, for the Tengu-jo paper we supplied to CITIZEN—and which is also used for the conservation of important cultural assets—we don’t use any chlorine. That only makes the careful preparation and treatment of the ingredients all the more important.

So the crucial thing in making high-quality paper is how you prepare and process your ingredients?

Absolutely. There’s no uniquely special piece of equipment or special method. It’s just a matter of whether you’re prepared to put in the necessary time and effort. We are—and that’s why we succeeded in producing this incredibly thin washi.

I would never say “no” to our customers.

Their demands led to us making this ultra-thin washi.

You mentioned something just now about Hidakawashi’s Tengu-jo paper being used in the conservation of cultural assets?

Originally, we were 99% an OEM, making shoji paper screens for other companies to sell under their own brand names. Times changed and demand for washi declined, so we started asking ourselves what we needed to do to survive and what it was we were best at. That’s when we realised that thinness was the thing that made us special. The next question we asked was, “Okay then, which sector will see value in our thin paper?” We happened to hear that conservators and restorers often stuck thin paper on top of paper that had grown brittle with age, and that’s what really kickstarted everything.

Did the people in the conservation and restoration business approach you?

Very far from it. In those days we didn’t even have a company brochure. What we did was to stick some washi into a clear folder, then go through the phone book (the Internet was not so widely used back then) and send out samples. The business started getting going when the products we’d sent out elicited a response. The turning point was when we got our first inquiry from a state institution. They wanted to know if we had a slightly thinner washi. It was with them that we developed this ultra-thin Tengu-jo paper.

Was it a struggle to make the paper even thinner?

When paper is thin, it’s very hard to produce a continuous and unbroken roll. It tends to develop holes and rips. We had to keep adjusting the tightness of the different components and the pressure of the papermaking machine. It was quite an ordeal to maintain the proper thinness and take the paper all the way through to the drying stage.

It’s impossible to do any testing when the factory is operating normally, so what happened was that a group of volunteers, most of them young, would get together in the factory late at night or on weekends when there was no one else around, and stealthily run the machines. At the start, we could only manage a weight of 3 to 4 grammes per square metre, but over time we made the paper thinner. After two years or so, we were down to 0.02mm and 1.6 grammes. Without a doubt, it was the strict demands of our customers that forced us to upgrade our technology and create this ultra-thin washi. We learn something from our customers every day.

Does the fact that you make the machines as well as the washi play a part?

Definitely. We use off-the-shelf motors and bearings, but the body of the papermaking machine is mostly custom made. I remember explaining what kind of paper we wanted to make to this enthusiastic old craftsman at the steelworks, and we kept the discussion going all the time he was working on the machine. Making washi really starts from the construction of the papermaking machines, so it’s a genuine team effort. We get all sorts of helpful input from other people and we convert that input into paper! That’s still how we operate today.

Your efforts paid off. Your paper is now used not just in Japan but all around the world.

Indeed. Me making multiple visits to galleries and museums around the world and giving demonstrations has proved to be very worthwhile—the Louvre, the British Museum, the Metropolitan in New York… Thanks to that, people from different countries, different cultures and with different languages reach out to us. They’re all amazed at the thinness and the uniformity of the paper we make.

We are proud to make the washi for this watch dial.

What did you think when you got the commission from CITIZEN?

At the start I was like, “What? Use washi for a watch dial? You must be kidding.” But after hearing the enthusiastic explanation of the person in charge, it became something I really wanted to do. We talked the whole thing through. Now I can say it’s a job I’m proud to have done.

Did CITIZEN make any specific requests?

People talk about Tengu-jo as a single category of paper, but the plant ingredients can come from different places and there are different methods of boiling it, different methods of bleaching it. The same’s true for dyeing the washi. Do you dye the actual fibres or do you add the dye later? There are endless types and permutations. CITIZEN was emphatic about wanting to use Japan-grown kozo mulberry and highlighting the beauty of the fibres, so we used a manufacturing method that would achieve those two things. Because washi made from mulberry has long fibres, it’s not very light permeable, so we had to figure out what thickness would best let light through. You’ve got to find the right balance between the thickness of the paper and the ability to charge, so we produced a ton of samples and CITIZEN made their selection from literally hundreds. The main washi CITIZEN opted to use is a very thin and attractive Tengu-jo. They’re also using a washi called Unryu paper, which stresses the fibrous quality of the paper, and colour washi too.

What did you think when you first saw the finished watch featuring your Tengu-jo washi dial?

I thought CITIZEN had done a great job in foregrounding the physicality of the fibres. You could tell it was washi at a single glance. It made me feel that all the work we had put into the project was worthwhile. There was no sense of incongruity. CITIZEN did a great job of merging the material character of washi with the atmosphere of luxury. And it wasn’t just about the dial. They explained to me how comfortable the bracelet was on the wrist and how there was a special coating on the glass to enhance visibility. I was mightily impressed. “This is not just about the washi,” I thought to myself. “These big Japanese companies have the most incredible technologies.”

You have supplied CITIZEN with several different kinds of Tengu-jo paper. Which model was the most memorable for you?

The one that made the strongest impression on me was the black dial model, the first one in which our washi was used. In the indigo model, the indigo was truly gorgeous…. More than the paper, our focus was on getting just the right hue of indigo for the watch. Since the dyeing master was an old pal of mine, I have vivid memories of the whole experience.

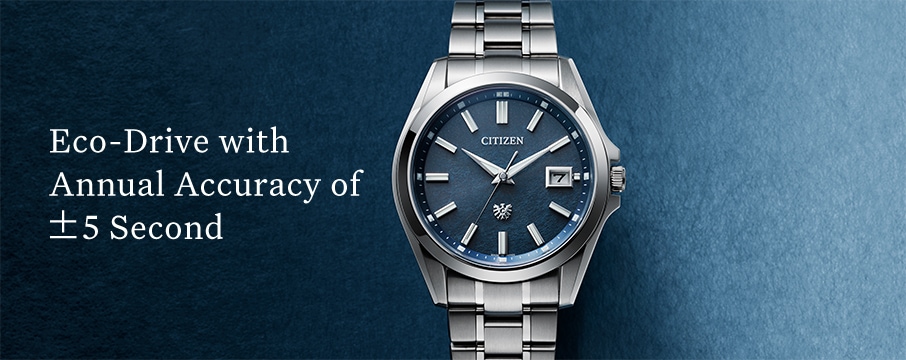

AQ4091-56E

Special Model featuring Tengu-jo paper

* Japan-only model. Not for sale in other countries.

Washi is a word that everyone everywhere understands.

Through washi, we can communicate the best of Japan to the world.

Your Tengu-jo paper is used in more than 30 countries worldwide. What are your future plans for it?

I often visit museums, galleries and libraries around the world to promote our washi. We may all have different cultures and languages, but the word washi is known everywhere, and everybody uses washi for conservation and restoration. What should we do more of? I’d like our company to become a hub to promote Japanese technology and culture to the world …not just washi, but the tools and brushes used in making it, CITIZEN watches, and so on.

Finally, what would your message be for customers of the Tengu-jo dial model?

I’d say that it’s a watch that works well for formal occasions and is also a great conversation starter, as in “Did you know that the dial of my watch is actually made of washi paper?” More than anything, I’d urge everyone to just take a moment to appreciate the beauty of the product. A dial that foregrounds the beauty of washi as a material is something quite unique. This is a work of technology and craftsmanship Japan can be rightly proud of on the world stage. I would urge anyone who has not yet seen the watch to go and have a look at it.

About

The hand that makes the washi for the dial…

The hand that inspects the materials…

The hand that sketches the design…

The hand that assembles the watch…

Aspiring to be an integral part of your life.

In the pursuit of the next ideal in timekeeping,

The CITIZEN has a passion for making beautiful things.

The living embodiment of superior craftsmanship,

Our watches pass through a succession of skilled hands

Before reaching their ultimate destination:

the wrists of the wearers.

In Hand to Hand Story,

We highlight all the expert hands,

So dexterous, sensitive and thoughtful,

Required for the complex process of watchmaking.